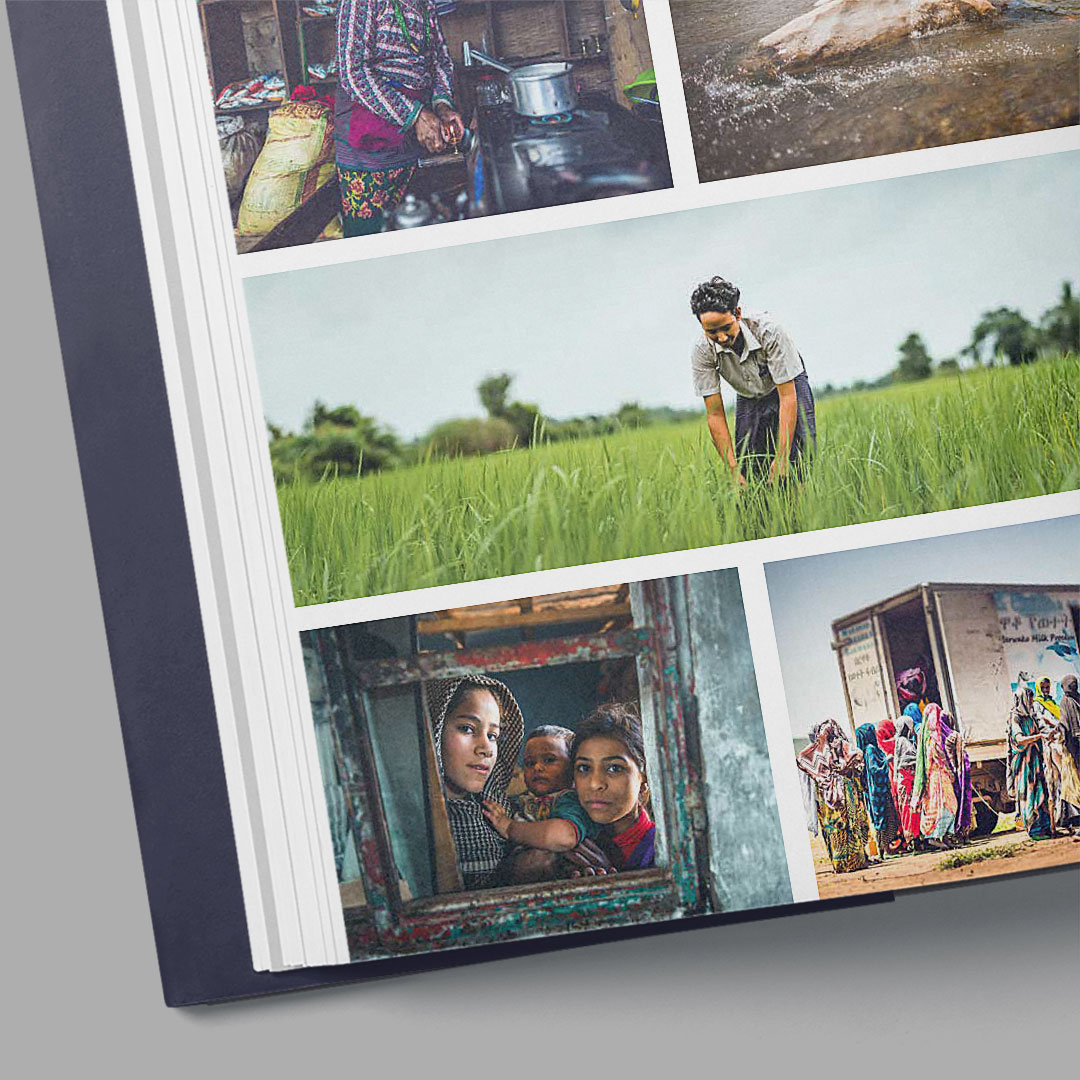

*Adapted from my forthcoming book Journey: A photographer’s retrospective on finding hope in the world’s hardest places.

First, let me be clear: the indescriminate killing of innocent civilians is pure evil. I know what I would do if I were forced by bad actors into defending the lives of my family or myself, and I wouldn’t hesitate.

But step back for a moment. Every time I shoot in a conflict or challenging area I wonder how differences could be handled so they don’t escalate into a situation like that of Cain and Able, the first recorded instance of murder according to Judeo-Christian tradition. Everywhere I have been (including the streets right outside my own front door), the use of violence against enemies seems to be the accepted norm and method of resolving conflict. We live in a revenge society! Sadly, this cycle of violence never seems to end. When I look at history and current world events, like the recent Israeli versus Hamas war, I’ll admit it feels hopeless.

Still, is there a way of dealing with our so-called enemies that brings hope and reconciliation rather than pain and destruction? From what I have seen and experienced, I would suggest perhaps there is: kill them with kindness.

“Someone had to do something sometime,” Joseph Heller writes in his classic novel Catch 22. “Every victim was a culprit, every culprit a victim, and somebody had to stand up sometime to try to break the lousy chain of inherited habit that was imperiling them all.”

When Heller wrote Catch 22 he likely would have meant “inherited habit” to mean apathy. Today it could be broadly interpreted as using violence to solve conflict. This chain must be broken. (For a convincing argument on why, I recommend reading Gary Haugen’s excellent The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence.)

But how can this be done? It’s clear that the “someone” Heller is talking about is actually me. Maybe even you. It’s crystal clear to me that “stand up sometime to try” translates today to “kill them with kindness.” In other words, to offer grace. To love your enemy.

In many ways the culmination of my career to date was my encountering the Taliban on a September 2023 shoot in the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. It took me far beyond the Three Bs and into the uncomfortable terrain of loving my enemies. Each time I came face to face with a Talib, I put my hand on my heart, nodded my head and said Salaam Alaikum! (peace be upon you). Why? Because there are very few things as powerful as greeting someone kindly in their own language. It breaks down walls. It opens a way for relationship. And it communicates a simple but profound “I see you.” Doing this was the perfect way to deflect all kinds of potential problems. It cost me nothing but maybe my own pride (a good exchange). It built a bridge where there wasn’t one. It was loving my enemy.

One time this played out was when I was in a car with my host and a work associate going to dinner at an expatriate’s house in Kabul. As we were parking, a Talib came out of the house next door and walked directly in front of the car. He was carrying an AK-47 (like they all do) and was in a hurry. When he looked up, he made eye contact with me and stopped, his hand moving to his weapon. I smiled, dipped my head, put my hand on my heart and mouthed Salaam Alaikum. Immediately his posture changed. He smiled back at me and went on his way.. Again, this deflected all kinds of potential problems. But I think it was bigger than that: there was now a bridge between so-called enemies. We had had a moment. My guess is he felt a small measure of respect, one of the hallmarks of love. It cost me nothing. It didn’t communicate any sort of capitulation or abdication of my morals. It just said, “I see you.” That’s loving your enemy. That’s how to break the lousy chain of inherited habit.

Jesus of Nazareth was the master at this sort of thing. He modeled these bridge building moments so well that it’s hard not to want to follow the lead. So yes, call me a Jesus follower. That man operated in a tradition jam packed with the lousy chain of inherited habit—but he knew the power of the ancient writings well, and one in particular, a proverb: “Good sense makes a man slow to anger, and it is his glory to overlook an offense” (Proverbs 19:11 RSV). The more I practice giving grace like the bearded man from Nazareth did—and I will admit I am far from “practiced” at it—the more astonished I am at the results. Suspicions melt away, and our great differences seem far less threatening. Smiles break out where there was once only anger. And hope takes root.

Again, please don’t get me wrong. The Taliban by most measures (like any extremist group) are indeed bona fide “enemies.” All you have to do is a quick Wikipedia search on the word Taliban and you will know why, if you don’t already. I certainly don’t like how they treat women or rule with impunity. Of course, they don’t like how my people tried to control their homeland. In fact, both sides in that war (and all others) have committed completely unjustified and unpardonable acts of violence, none of which I personally condone. The problem in situations where the shooting has stopped like this is that even basic kindness runs deeply counter-culture to the lousy chain of inherited habit we’re all stained with. We’re just angry, and we’re all guilty.

Kindness and a measure of respect stops this chain in its tracks. Love breaks it. It breaks the stupid, lousy emotional poverty so many people are trapped in. It breaks the lousy authoritative madness so many leaders impose on their people here in the United States and abroad. It breaks the vapid way we are treating the earth and each other. You fill in the blank with what is lousy in your world. Love, starting with kindness, respect and grace, will break the habit if we choose it.

Don’t mistake this kind of love for blind tolerance or avoiding conflict at all costs. Grace has nothing to do with appeasement, which doesn’t work and has its own special kind of lousy chain of inherited habit (just ask the people who signed the Munich Agreement in 1938). Grace, however, totally transcends this way of thinking and acting, catapulting love into a category where it stands unmatched in its ability to heal and reconcile (just ask the people who signed the Good Friday Agreement in 1998). In short, love creates change that can scarcely be believed.

Case in point: While I was shooting in Ukraine during the Russian invasion of that country in September of 2022, I came across what I can only describe as a miracle, a situation where love broke all the rules in the midst of a war zone. My host there was a huge mammoth of a man—a former national Grecco-Roman wrestling champion who had given himself to working on behalf of Ukrainian refugees by organizing food distributions. Everyone knew him and how he was no longer motivated by defeating wrestlers but by loving his adversaries. When we took a convoy of vehicles for a food drop from Romania across the border into Ukraine, we all knew the risks but went anyway. Upon arriving at the drop location, we couldn’t believe our eyes: there were thousands of hungry refugees waiting patiently in line for us. Thousands. We estimated more than four, maybe close to five thousand. The problem was we only had 2,000 food bags in the trucks.

We looked at each other and knew this would have to be a Jesus moment like the feeding of the four or five thousand recounted in the Bible. I think you can guess what happened. When every person had been served that day, there were still bags of food in the trucks. We can’t explain it. But it’s true. Love had won the day.

Let me sum this up with a few words my friend Thad Cockrell recently wrote in his song Texaco:

I want you to know, I want you to believe, in something much greater than you and me.

And I’m pulling for you no matter where you go, if it’s far again or fast or slow.

There’s a love that covers everything, and everyone. May God’s love cover everything and everyone.

The leading out, the coming home, the ones who have, the ones who owe, the ones who believe, the ones who don’t, the rise and fall—it covers it all.

This is our calling on the journey: to be the ones that provide the cover that breaks the cycle of madness. The ones with the courage to go against the grain and build bridges no matter how small they seem. The ones who have the guts and gumption to love our enemies in the face of all logic or adversity. That’s me. That’s you.

Like this:

Like Loading...